Kidnappings in China, 100 years ago and now — Q&A with James Zimmerman

It’s becoming more and more difficult for investors, journalists, and scholars to get information about China. How does this affect doing business there? And what can we learn from the story of a hijacked train in Shandong in 1923?

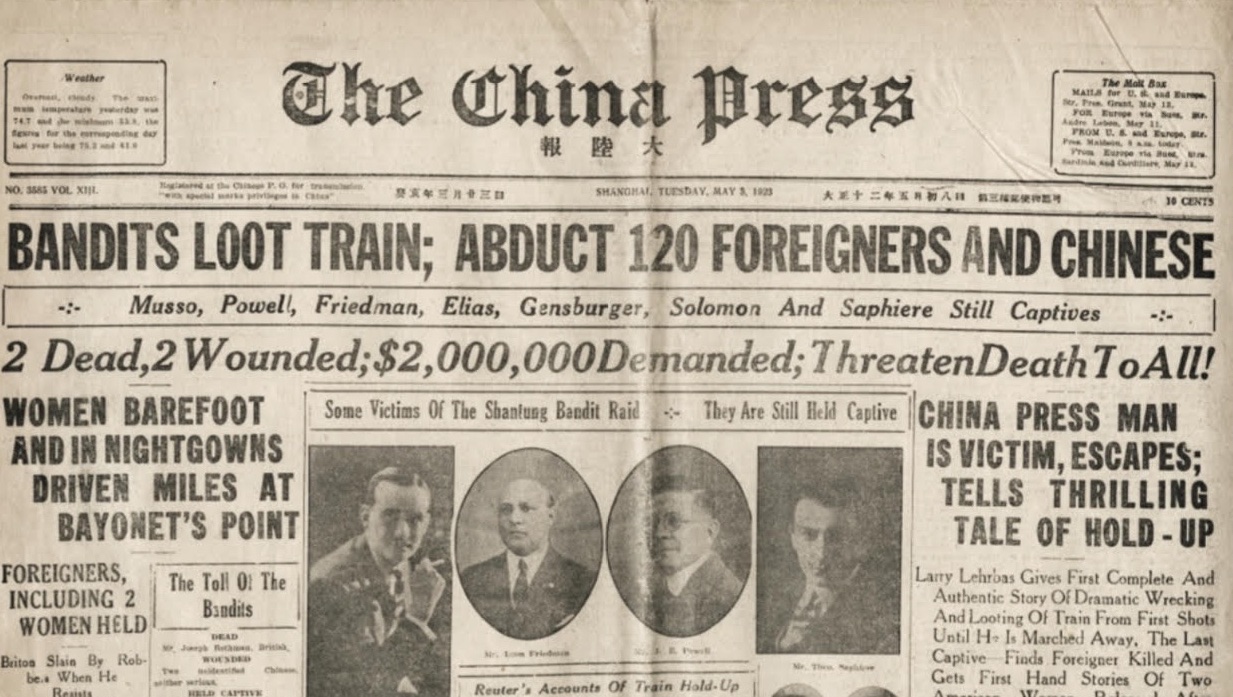

James M. Zimmerman is the author of The Peking Express: The Bandits Who Stole a Train, Stunned the West, and Broke the Republic of China, which recounts the story of a train from Shanghai to Beijing that was hijacked in 1923. The more than 300 passengers on board — including 30 of the richest foreigners living in China at the time — were kidnapped by a gang led by bandit and revolutionary Sun Meiyao (孫美瑤 Sūn Měiyáo).

Zimmerman is a lawyer who has lived and worked for more than 25 years in China, where he has advised companies and individuals who have to deal with the hard end of China’s political and legal systems. He’s also written several books on legal topics, and served four terms as the chairman of the American Chamber of Commerce in China.

We recently chatted via video call about his new book, China’s economy, and how safe it is to do business in China. This is a lightly edited, abridged transcript of our conversation.

—Jeremy Goldkorn

What drew you to the story of the 1923 train hijacking? Was something resonating about a bunch of foreign elites being kidnapped on a trip through rural China? But why did you decide to write? It’s your first work for a general audience, isn’t it?

Yeah, my day job is addressing issues that can include people who are detained, hostage diplomacy, and things like that.

I came across the Peking Express story about 10 years ago during some research that I was doing. I was fascinated by the history of the use of kidnapping for economic reasons, and I realized it’s not something that has been addressed much in the media, nor has anyone written a book about the topic in recent years.

There have been articles in Chinese, and many of them [are trying to decide] if the bandits were heroes or not.

As I started digging into archives in China, and in the U.K. and the U.S., I started coming across a number of the family members, descendants of those who were actually on the train, and descendants of the rescuers, and the bandits themselves. The more I researched, the more I realized that the families kept records. There were hundreds and hundreds of letters and diaries and statements, memoirs and…

One gentleman, who was a U.S. Army major at the time of the incident, kept a 175-page diary of the 37-day hostage crisis, a very detailed description of everything that he went through, and what he talked about with the other hostages whom he was with.

That was just one resource, and there were many other diaries that had never been published before, and a lot of the letters that were going back and forth between the government negotiators as well as the hostages. So I knew that I had a story to tell. The book is really based upon a lot of the family diaries, a lot of the records that had never been published.

And of course, it was also a media story at the time. For the full 37 days, the media was writing story after story after story. Part of that was because there were a number of correspondents on the train who either became hostages or escaped.

So there were a lot of people writing about it when this incident was happening. But then the story just got buried in history, with the Japanese invasion, World War II, the Civil War, the Cultural Revolution. It just seemed to be forgotten.

So let’s come back to the year 2023, exactly 100 years after the train hijacking. What are the resonances?

Hostage diplomacy is very much alive just as it was in 1923.

And just like now, the government back in 1923 was very quick to label people as bandits or anti-social. It’s a way to summarily detain and convict somebody, or to execute them. The government today is still very quick to label people as troublemakers…

Picking quarrels and provoking trouble? Xúnxìn zīshì 寻衅滋事, right?

Yeah. The bandits of 1923 are the people who are getting labeled as troublemakers today. And it’s an issue of due process.

So the other thing in Peking Express, is I describe how the Chinese government at the time was also trying to manage the message with the foreign reporters. In 2023, things haven’t really changed in that regard as well.

Right.

In 1923, they were trying to micromanage the stories and the message. They didn’t want journalists to report anything negative about what was going on with the hostage crisis. In 2023, it’s the same thing, the way the Chinese government is trying to micromanage the media, both the domestic and the foreign media.

One message Beijing is trying to manage right now is about the economy. There have been reports in recent months that the Chinese government has requested analysts to not say depressing things about the Chinese economy, and the government stopped releasing youth unemployment numbers, apparently because the numbers were so bad.

But the mood outside of China is almost uniformly negative with a broad consensus that China is at best 10 years of Japanese-style stagflation and at worst about to collapse.

You’re in Beijing. How does it feel to you?

What they don’t realize is that when they try to manage the message, what they generate is a lot of speculation. The more they micromanage it, the less information is out there, and people start speculating and it creates a whole new storyline. If they were just transparent and allowed all the data out there, including the jobless rates for college students, investors would digest it and make their decisions based upon full transparency.

But unfortunately, what they end up doing is when they try to gloss over problems, they just create more uncertainty.

I think overall on the ground today, there is clearly a trust deficit and an information deficit. So we really don’t know what’s going on.

Including inside China? Do you think Chinese people are feeling a trust deficit?

Yeah. People on the ground see that there’s a lot of uncertainty. That’s why they’re not really spending a lot of money.

That’s why you see more and more high-wealth people moving money offshore — because of the uncertainty. And it’s being driven by not enough information.

But I’ve been traveling [over the last few months, to places like] Yantai [in Shandong Province]. The trains were packed, a lot of people traveling, the restaurants were packed, the streets were packed. So why can’t they get that story out there?

That people are domestically at least spending money on something. They might not be spending money on real estate or electronics, but they’re spending money on holidays, but overall there is clearly a lack of accurate information, and driven by trying to manage the trying to withhold information. And unfortunately, that just again creates a lot of speculation and it creates a whole new storyline.

Let’s go back to the subject of your new book: foreign hostages. One of the questions in the community of people connected to China in the United States and Western Europe is the simple question: Should you go back to China? Is it safe?

The two Michaels, Cheng Lei, and many others…The new anti-espionage laws. The raids on foreign research and due diligence companies. The shutting down of databases and archives to foreign people and entities…

How do you look at these questions right now?

What makes people nervous in the business community? Again, it goes back to a lack of information.

Over the last year, the raids on the due diligence firms and consulting firms, there wasn’t a whole lot of information. People were thinking, “My God, these are investigations focused on national security. We don’t know what’s happening. There’s no due process. People are getting detained.”

For example, the Mintz case, which people were worrying about, was about national security reasons. It was not a criminal investigation, it was for some pretty low-key, improper surveying. It was a civil penalty. It wasn’t like the two Michaels.

It was more of a compliance issue.

But there are real concerns on the ground, and people are worried.

And do you yourself feel safe working in China?

I don’t feel that I have any kind of special protection or special privilege, but as a lawyer and having lived and worked in Beijing for 25 years, I do understand the importance of compliance.

And so, myself and the people I work with, we spend a lot of time making sure that we’re in full compliance. I don’t want to say, “Yeah, I feel safe, I feel protected,” but we do everything we can to make sure that we don’t run into any issues or any problems.

In terms of my safety, probably the biggest risk for me is that I still drive in China…

That’s a risk factor! You definitely stand a greater chance of having your brains on a windshield than you do of getting locked up in China.

I don’t not worry about getting locked up or being detained. But I’m very cognizant that we have compliance obligations and we do everything we can to make sure that we are in. Our clients are in full compliance.