‘A desperate attempt’ — Phrase of the Week

Chinese consumers are stockpiling salt in reaction to news of Japan’s release of treated wastewater from the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

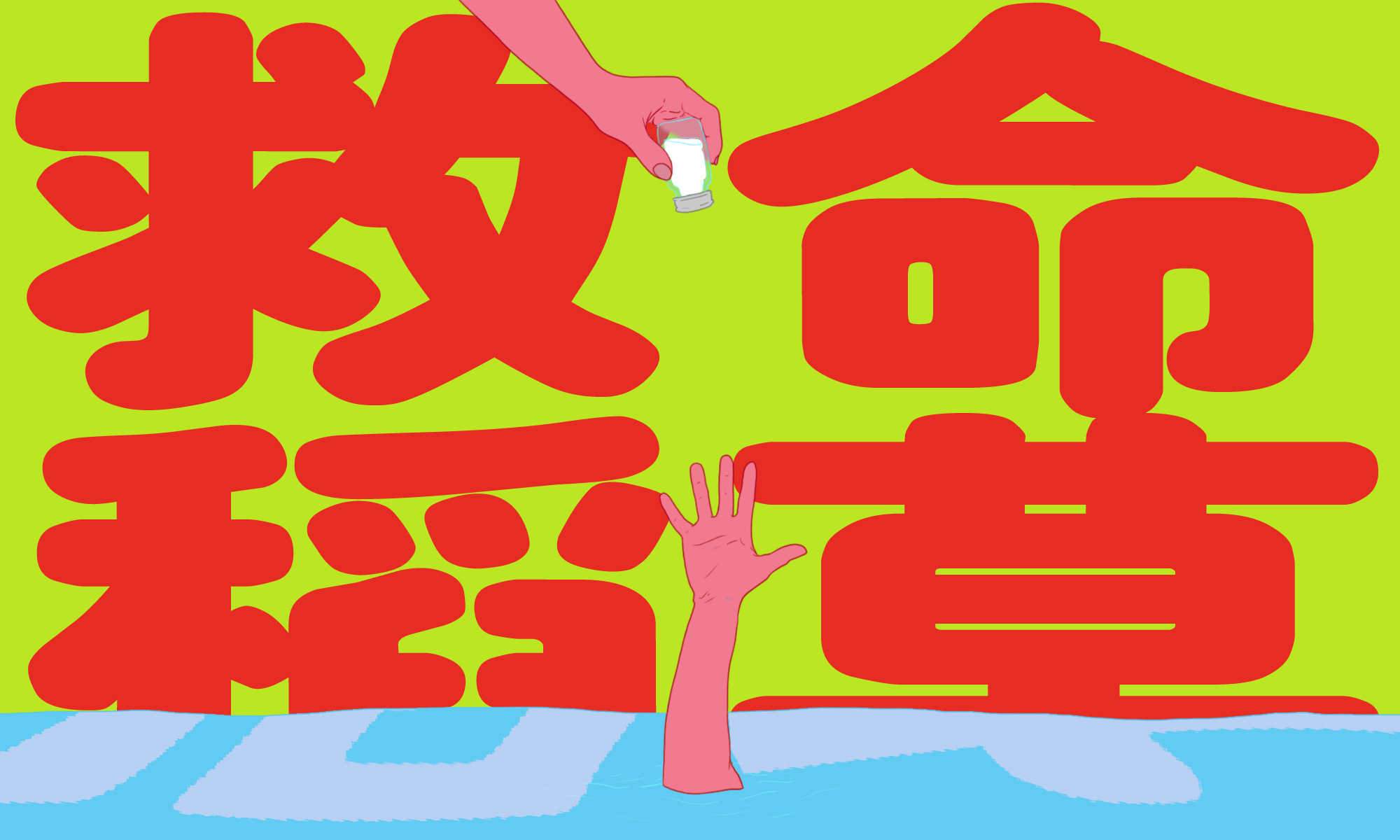

Our Phrase of the Week is: A desperate attempt (救命稻草 jiùmìng dàocǎo).

The context

Consumers in China and other countries across Asia have fiercely objected to Japan’s controversial release of treated wastewater from the Fukushima nuclear power plant, which began on August 24.

Some consumers in China began panic-buying salt (抢盐 qiǎng yán), hoarding it amid fears of future contamination and a mistaken belief that iodized salt (加碘盐 jiādiǎnyán) can ward off the effects of radiation. It’s reminiscent of the panic-buying that happened in the country after the nuclear disaster in March 2011, following similar rumors that have been circulating online.

China’s state-run National Salt Industry Corporation, the world’s biggest common salt maker, urged people (as it did in 2011) not to panic-buy in a statement released on August 25:

China’s table salt supply is 87% mine salt, 10% sea salt, and 3% lake salt. Salt mined from land and lakes, which account for 90% of the total, are not affected by sea discharge.

我国食盐产品结构占比为井矿盐87%、海盐10%、湖盐3%。占比合计九成的井矿盐和湖盐,并不受排海行为影响。

Wǒguó shíyán chǎnpǐn jiégòu zhànbǐ wéi jǐngkuàngyán 87%, hǎiyán 10%, húyán 3%. Zhànbǐ héjì jiǔchéng de jǐngkuàngyán hé húyán, bìng bú shòu páihǎi xíngwéi yǐngxiǎng.

This calmed consumer concerns. But an opinion piece in Singapore’s largest Chinese-language news outlet, Lianhe Zaobao, suggests why some Chinese consumers were panic-buying in the first place:

It is true that the Chinese government firmly opposes Japan’s discharge of nuclear wastewater into the sea, but there is a lack of scientific and systematic discussion, and the Chinese people have long been in an opaque and asymmetric information environment. They are more likely to be irrational when faced with such emergencies and controversies. Perhaps hoarding goods is the only practical measure they can take as a last desperate attempt to find security.

诚然,中国官方反对日本核废水排海的态度坚决,但缺乏科学和系统的论述,而中国民众又长期处于信息不透明和不对称中,在遇到突发事件和争议课题时,更容易失去理智陷入混乱,或许用实际行动囤货才是他们捍卫内心安全感的救命稻草。

Chéngrán, zhōngguó guānfāng fǎnduì rìběn héfèishuǐ páihǎi de tàidù jiānjué, dàn quēfá kēxué hé xìtǒng de lùnshù, ér zhōngguó mínzhòng yòu chángqī chǔyú xìnxī bútòumíng hé búduìchèn zhōng, zài yùdào tūfā shìjiàn hé zhēngyì kètí shí, gèng róngyì shīqù lǐzhì xiànrù hùnluàn, huòxǔ yòng shíjì xíngdòng tùnhuò cái shì tāmen hànwèi nèixīn ānquángǎn de jiùmìng dàocǎo.

And with that, we have our Phrase of the Week.

What it means

A desperate attempt is a four-character idiom, which directly translates as “saving life” (救命 jiùmìng) and “piece of straw” (稻草 dàocǎo).

Often translated as “a drowning man will grasp for straw,” the idiom expresses desperation at a situation in which there is no hope. It’s a last futile attempt before the inevitable drowning happens.

It was originally an English idiom first used in 18th-century America, according to Bartlett Jere Whiting (1904–1995), a professor at Harvard University who specialized in middle English and English proverbs.

Therefore, Lianhe Zaobao is suggesting that there is not enough information for consumers to make rational decisions, and therefore they have no option but to make desperate decisions such as panic-buying salt.

A desperate attempt is similar in meaning to another Phrase of the Week, Try anything in a desperate situation (病急乱投医 bìng jí luàn tóu yī), which can mean making bad choices, or doing the wrong thing in a crisis.