Liuyu Ivy Chen weaves together Marxism, Sharon Olds, James Baldwin, and Chinese Communist Party lore in this poetic and unflinchingly honest essay about how she, as a child in an anonymous Chinese city, viewed the 9/11 attacks. And how she, as an adult now living in New York, views her younger self.

When news of the 9/11 attacks reached my school in a small city in central Zhejiang Province, we were in the middle of our morning lessons. I remember the stunned and slightly rapturous look in our teacher’s eyes after he was called outside and given the news, which by then was already 12 hours old. In the gray granite-paved hallway, he drew a deep breath, gave an elongated nod, and rubbed his smooth chin, before he slowly stepped back into the classroom, where we were chatting, dozing off, or snacking away. My best friend Lu and I were throwing crumpled wads of notes to exchange gossip.

“Hurry, turn on the TV. Big news,” the teacher said, rubbing his hands vigorously and ignoring our mischief. “America is under attack!”

Helicopters, smoke, and the crumbling towers appeared on the screen. This was a re-broadcast, but to us it may have well been happening live. Serious-faced Chinese commentators offered their scripted interpretation. I kept my eyes glued to the scene, having a hard time distinguishing real-life news from a Hollywood movie. Underneath my shock emerged a thought: What did America’s fall mean for China’s rise? How come I felt relieved? China would no longer measure up too short, for we could now catch up while America cleaned up its debris. Although very few people I knew would openly betray these feelings, I could sense them spreading through our neurons in such uplifting waves that we had to make a noticeable effort to tuck them under our skin.

I was 11, with a stony heart. If only America had not been so hostile toward China, I thought — joining the Siege of the International Legations, making excuses for its bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, continuing its support for Japan and Taiwan, etc. — it would not have brought such bad karma onto itself.

It was only after I lived overseas that I found out about the censorship of the 9/11 coverage by Chinese state media, and discovered the shame and guilt that would gnaw on those who had a chance to unlearn what they were taught.

One summer day in 2002, an American diplomat visited my middle school, and all the theoretical animosity on campus evaporated. Most of us had never seen a foreigner, and we were all enthralled by a white man’s presence. The occasion even warranted a special entry in my diary:

“Wow, he is so tall and walks with such a gentlemanly gait. His blue eyes glow with an exotic light and reflect deep emotions. Like a dream, we talked to him in English, finally putting what we’d learned into use. The diplomat flew for 20 hours to China. Incredible! Suddenly, I feel a longing for a foreign county.”

After the diplomat’s visit, my school organized a Cambridge English-language summer camp, where enrolled students had the privilege to experience immersive English learning with an American instructor. The spots were quickly filled despite the exorbitant tuition fee: over 10,000 yuan ($1,360) for one month. English-speaking skills were key for success in the new China. Mu, my rural classmate, convinced his parents to foot the bill. Lu, the only child in her well-to-do urban family, went as well. I was dejected that my mother, a self-made entrepreneur struggling to raise three daughters in the city, decided against it. (I never had a chance to talk to a native English speaker until I left my hometown.)

In 2012, after I graduated from college, I came to New York City to study poetry on a full-ride scholarship. The America I had imagined in abstract terms suddenly popped with sound and color, like raw fabric decanted from a dye vat, a swift-moving reality too slippery to grasp. I rented a rooftop room in a prewar building on Bleecker Street from an old Malaysian lady, who was a couples therapist — sometimes I saw her performing hypnosis on her clients. Daily, I passed a homeless poet who camped outside my building, mumbling and ambling, as if mocking the bourgeois foreign poet living upstairs. I was equally fascinated by a street pianist who played classical music on a beat-up grand piano in Washington Square Park — toddlers danced around him, dollar bills tumbling into a plastic bucket. All these realities challenged the Marxist theory I’d absorbed in China, that 物质是精神的基础 (wùzhí shì jīngshén de jīchǔ) — matter is the foundation of spirit. In the nothing-is-impossible land of America, a single woman could cure a couple’s marriage problems by putting them to sleep, and a penniless poet or pianist could pursue spiritual enrichment while contributing to the community’s cultural fabric.

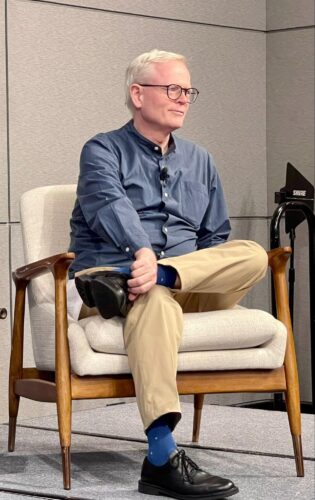

Twice a week, I turned into a tree-lined street in Greenwich Village and walked past the former residences of Mark Twain and Emma Lazarus to arrive at my program’s quaint building. I took classes from leading American writers and sat alongside classmates from privileged backgrounds. I was the only Chinese student, the first in the program’s history, a total foreigner to my peers, a bent feather poking out from the plumage of America, Mother of Exiles.

On September 11, 2013, in a seminar room with white wall-to-wall bookshelves, my poetry teacher, Sharon Olds, invited us to share our experiences of 9/11 — where we were and what we were doing on that day. I tensed, shifting in my seat. A dozen of us sat around a long white table, lost in thought, philosophizing an acute American pain. Using her carefully considered and slowly articulated English (she so charmingly pronounced “white” as “h-white”), Sharon recalled with starry eyes how New Yorkers turned to poetry after the tragedy, how poetry never enjoyed such popularity, how people extended trust and support to strangers, how the city never felt so together. Where the superstructure of reason fell, amorphous poetry filled.

In China, poetry was the superstructure. Politicians were, first and foremost, poets in ancient times. Even the modern tyrant Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 was a decent poet. My illiterate grandma could recite poems in her crisp local dialect. Most of us have dozens, if not hundreds, of poems stored in our memory, ready to roll off our tongues to describe the indescribable. From Sharon’s words I gathered that in America, poetry stood piteously outside the popular imagination, an afterthought, a decoration, at best a therapeutic device perhaps not dissimilar to hypnosis. The end goal was to cure, to feel better, to be useful. But only in negation of utility did poetry speak freely, casting an eternal beam into the firmament of all ages. Only in negation of utility could poetry hope to escape the firm grasp of political indoctrination.

When it was my turn, I was flustered, failing to clean up my thoughts — non-linguistic masses congregated in the corner of my brain. I blushed, spitting out some variation of the karma theory: The higher you build, the harder you fall. My cruel, clueless answer was kindly ignored by my classmates.

When the 9/11 Memorial & Museum in Lower Manhattan opened in 2014, I paid a visit. Two solemn pools, nearly 3,000 names. A rose here and a flag there, tenderly pinned on a missed name. My tears welled up as I felt my entire being pulled by the sound of the waterfall cascading down the bottomless pool. Yet my mind went blank. Afraid to linger too long as a trespasser on others’ grief, I turned and left the site.

I first learned about Manhattan in a textbook essay titled “Night Scene in Manhattan” in middle school. It was written by Dīng Líng 丁玲, whose accolades included a Stalin Prize. Ding was denounced during the Cultural Revolution, but her reputation was later restored, and her writing immortalized in our educational materials — in an authoritarian regime, one’s fate is so often flipped on a whim.

I first learned about Manhattan in a textbook essay titled “Night Scene in Manhattan” in middle school. It was written by Dīng Líng 丁玲, whose accolades included a Stalin Prize. Ding was denounced during the Cultural Revolution, but her reputation was later restored, and her writing immortalized in our educational materials — in an authoritarian regime, one’s fate is so often flipped on a whim.

Ding described a homeless man she saw when she visited Manhattan in 1981:

Look, there is an old man sitting on the ground at a street corner, his body hunched over, his eyes half-closed. Pedestrians pass him by, headlights flash over him. Nobody looks at him, he looks at nobody. What is he listening to? What is he thinking? He is indifferent to his surroundings; people are more indifferent to him. What does he want? He seems to want nothing, just sitting there. What does he like to do? He does not seem like doing anything. Nobody needs him to do anything. He is sitting among the crowd in the street, relevant to nothing — not to the street, not to the people. But he is alive, he is a life, sitting in this lively street.

…

Old man, you can continue sitting there, eyes half-closed, body bent, looking dull and gray, decorating the glamorous Manhattan night. Farewell, Manhattan, I cannot stay here for long.

When answering reading comprehension questions during exams, in the same classroom where I saw on screen the Twin Towers collapsing, I elaborated: The author empathized with the homeless man whose plight arose from severe social inequality caused by capitalistic exploitation in America. If only this homeless man were born in socialist China!

I now live in NYC and see homelessness in a different light, a social issue that politicians, activists, and citizens openly debate; sometimes it is even a free-willed choice, as in the case of the vagrant poet. I recall with complex feelings how, in my teen’s eye, Manhattan was reduced to a foreign theater playing capitalism’s greatest hits, a textbook example of human degeneration and a symbol of American imperial iniquity.

While we were vigilant about capitalism’s follies in the West, we turned a blind eye to the widening inequality in China. Why did my rural classmates have to pay a hefty fee to study in the city? What were the conditions of the Sichuan, Guizhou, or Jiangxi migrant workers toiling in our factories? What did those heavily made-up women in the hair salons do to make a living? How did my cousin feel when she quit high school to work in the city and support her family in the village? Why did so many parents give away their daughters? How come homeless people in the street suddenly disappeared before internationally televised national events?

In the simply furnished classroom bedecked with Mao’s portrait and slogans, under fluorescent tubes covered by moths and grime, we absorbed communist ideas in our textbooks while the capitalist world outside unraveled at a scary speed. This resulted in a discrepancy so vast that it bred a culture of absurdity and apathy. Because we were conditioned to follow an authorized ideology printed, plastered, and blaring everywhere we turned, we gradually became divorced from our feelings and tone-deaf to individuals and events that challenged the worldview propagated by our superiors.

Yet all emotions need an outlet, so the Chinese System created heroes, martyrs, and model citizens according to the same mold, who could draw out our tears and divert our attention, orchestrating a collective sentimentality. We celebrated quasi-fictional martyrs like Léi Fēng 雷锋, Liú Húlán 刘胡兰, Qiū Shàoyún 邱少云, and Dǒng Cúnruì 董存瑞, who sacrificed their lives for the communist cause with unblinking decisiveness and suspiciously similar plots. In the case of Liu Hulan, she was portrayed as a devoted Communist Party member unfazed when captured by the enemy, the Nationalists.

“Why did you join the Communist Party?” the enemy asked her.

“Because the Communist Party helps the poor,” Liu replied defiantly.

“You are so young but so stubborn. Aren’t you afraid of death?”

“If I’m afraid of death, I wouldn’t become a Party member!”

Next, the Nationalists killed six of her comrades with a scythe in front of her. Undaunted, Liu walked toward the scythe and became a martyr. She was yet to turn 15. Her death saddened Chairman Mao, who, driven by a poetic urge, wrote a calligraphic couplet to memorialize her: “Great life; glorious death” (生的伟大,死的光荣 shēng de wěidà, sǐ de guāngróng). Ever since, Liu has been a role model for Chinese schoolchildren.

“Sentimentality, the ostentatious parading of excessive and spurious emotion, is the mark of dishonesty, the inability to feel; the wet eyes of the sentimentalist betray his aversion to experience, his fear of life, his arid heart; and it is always, therefore, the signal of secret and violent inhumanity, the mask of cruelty,” wrote James Baldwin in 1955. When I read his words in the comfort of my home near Baldwin’s former residence on West End Avenue, I felt hit by a brick. Although the socio-historical context that Baldwin — a Black American gay man who died in France before I was born — lived in and wrote from could not have been more different from mine, I found that his diagnosis of the American psyche also described what I felt while growing up in China.

In middle school, driven by a collective sentimentality, I once criticized those who violated the one-child policy in a writing assignment. “The one-child policy is now being implemented; control is underway. Only some families do not obey the law and have babies in secrecy. They’re selfish and grossly ignoring the future of the overpopulated earth,” I wrote with the ardor of a socialist and environmentalist, grossly ignoring my own identity as a third daughter in my family.

Another time, I turned in my friend Lu to our head teacher Mrs. Xu, citing Lu’s delinquency in fulfilling her duty as a class cadre — she forgot to sweep the floor that day. But the real reason, the deeper drive, was that I wanted Lu to be punished. She was petite and pretty, smart and special — she was what I was not. Impressed by my impartiality, courage, and self-sacrifice (by offering up my best friend), Mrs. Xu praised me profusely in class. Lu lowered her head and blushed in shame. Afterwards, we said nothing about the matter and resumed our friendship, but it never felt the same. She still waited for me after school to buy spicy malatang soup outside the gate, but her attitude cooled, and her patience thinned. She stopped throwing me wads of funny notes in class.

Slowly, my “inability to feel” and my “arid heart” progressed into “violent inhumanity,” exacerbated by teen hormones and the confusing dialectical Marx philosophy: “Everything has two sides” (任何事物都有正反两面 rènhé shìwù dōu yǒu zhèng fǎn liǎngmiàn). It all culminated in me penning an essay in high school defending Al Qaeda. “It’s not the first time I salute the terrorists with deep respect,” I wrote. I’d read an interview about the 2005 Amman bombings and was deeply moved by the organizer Tamimi’s seven-year-old son, who told his father that he would volunteer to become a suicide bomber.

“Such a small child, harboring such a terrifying idea. What a noble patriot! He could have enjoyed a carefree childhood bathed in his father’s love, but he only carries hatred, hatred! What makes the suicide bombers so fiercely fearless? It’s because they have an unwavering patriotic heart!”

My teacher graded this essay as “very good.”

In the decade since Sharon Olds’s class, I have been trying to peel my feelings and thoughts away from any dominant narrative, a multilingual, transcontinental, and cross-generational endeavor that seems impossible to carry out at times. “A Russian-American author once quipped that what Russians needed after perestroika wasn’t economic aid but a planeload of social workers, and this seems painfully true. One reason people find it so difficult to describe how they feel is that they have never been asked,” the journalist John Vaillant wrote in 2010. Likewise, what China needed the most after the Cultural Revolution was not economic reform, but a fleet of therapists to diagnose the generational trauma. A simple “How do you really feel?” might have released an avalanche of memories contradicting the Party’s account of history.

“Something very sinister happens to the people of a country when they begin to distrust their own reactions as deeply as they do here, and become as joyless as they have become. The person who distrusts himself has no touchstone for reality — for this touchstone can be only oneself,” wrote James Baldwin in 1963. When I read this with America in mind, I see American highways, fast-food chains, suburban homes, and dental offices, the utmost comfort and middle-class standard designed to bring convenience and eliminate pain. When I read this with the Chinese in mind, I feel the numbness required of an individual to quickly resolve personal and historical trauma and keep up with the swift flow of the masses. We Chinese chase far-flung poetic dreams against all odds, asked to endure a collective pain so much greater than our individual selves that we simply stop feeling.

When asked what death means, Confucius said: “I have not known life, how do I know death?” But poetry attempts to make sense of both life and death. Is that why so many New Yorkers turned to poetry after 9/11, to make sense of the living through sensuous words so they could better cope with the senseless deaths? Is that why Americans felt together for once, briefly, because fear and pain allowed them to be the touchstone of their own feelings?

Baldwin again: “To be sensual, I think, is to respect and rejoice in the force of life, of life itself, and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread. It will be a great day for America, incidentally, when we begin to eat bread again, instead of the blasphemous and tasteless foam rubber that we have substituted for it.”

Learning to be sensual is my way of fighting the tyrant that still lives in me, the tyrant who betrayed a friendship and was glad to watch the American towers fall, who was fed a dyed-red foam rubber of an ideology. I feel, thus the tyrant starves, and I am free.