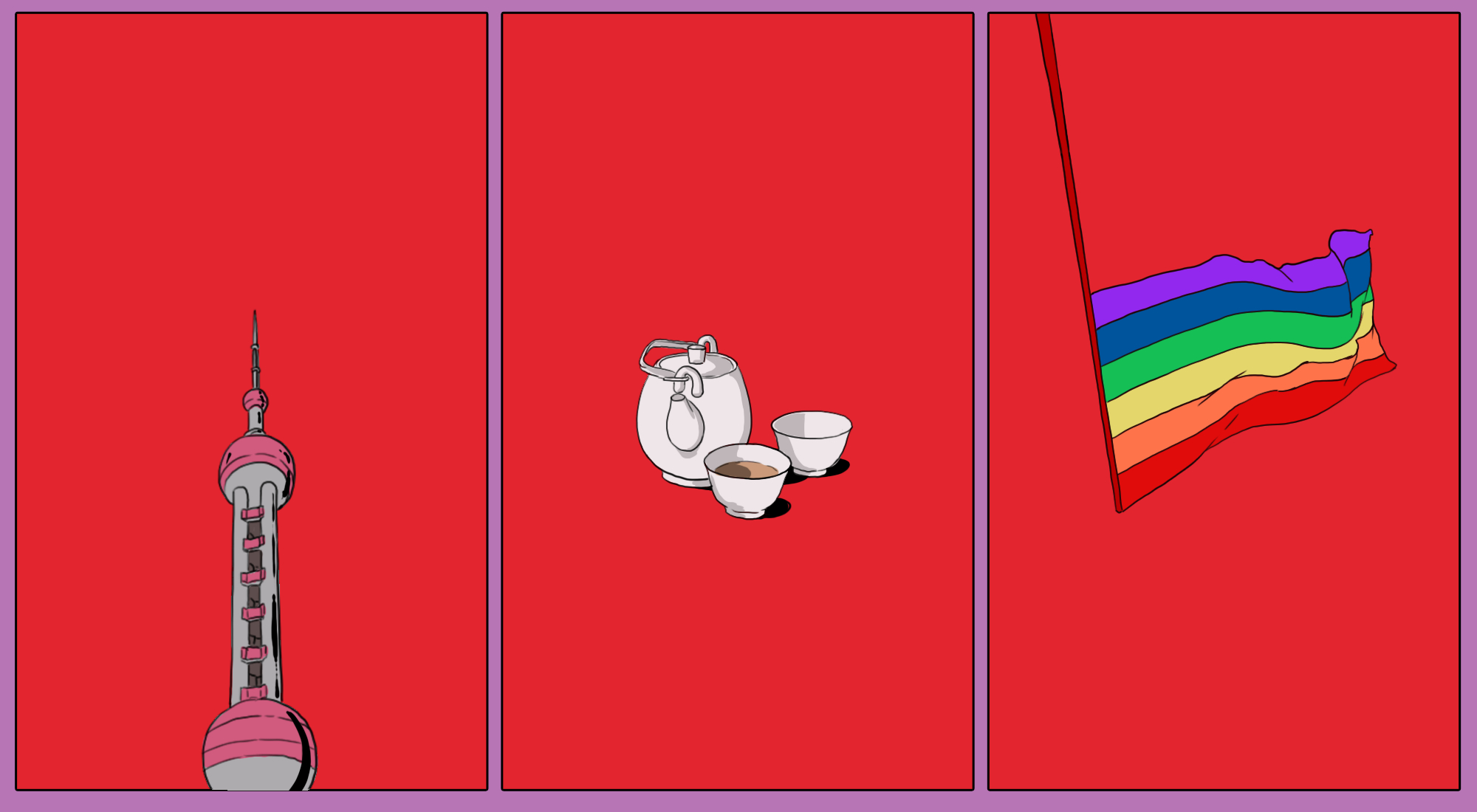

More info on ShanghaiPRIDE shutdown: Team members asked to ‘have tea’

"Drinking tea" in China is a euphemism for being interrogated by police.

After running for 12 consecutive years, ShanghaiPRIDE, an annual festival that celebrates China’s LGBTQ movement, announced abruptly last Thursday that it would cancel all upcoming activities as of August 14. In an email to its members, ShanghaiPRIDE claimed that it had to “protect the safety of all involved.”

The organization did not elaborate on what “safety” entails. But according to an assistant to ShanghaiPRIDE’s leaders who wished to remain anonymous, at least three people on the core team had been invited to drink tea (喝茶 hē chá) with police — a euphemism for interrogation in China’s political language. Team members don’t feel safe anymore, as they get random house checks and questioned by cops. “That wasn’t a big deal before it started happening more and more often,” the assistant said. Worse yet, ShanghaiPRIDE leaders used to know which officials they were talking to. “Now they are not so sure.”

On Weibo, people speculated that ShanghaiPRIDE crossed the line by partnering with foreign institutions. This might have roused suspicion from the government, given that China-U.S. relations have reached their lowest point in decades. But the assistant clarified that the U.S. consulate has not funded ShanghaiPRIDE over the past five years. Other consulates have helped little besides providing the venue for the festival’s movie screening.

The lack of explanation for ShanghaiPRIDE’s shutdown is emblematic of a bigger problem: In mainland China, the red line for LGBTQ-related topics is blurry. Officials regularly remove LGBTQ content from the public sphere without making clear the rules governing their censorship. On the screen, some films with same-sex elements escape official scrutiny, such as Beauty and the Beast and Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker. Others, like Lan Yu, which garnered the Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay awards at the Taipei Golden Horse Festival, are banned. In schools, some textbooks continue stigmatizing homosexuality, even though officials ceased to recognize it as a mental disorder in 2001. Courts have accepted but remain ambivalent on lawsuits over textbook homophobia.

When eight people first organized ShanghaiPRIDE in 2009, only two were Chinese. Ten years later, it attracted over 8,000 participants and 100 volunteers. Its shutdown is a huge blow to China’s LGBTQ activists. Indeed, the festival has been supporting LGBTQ people from the bottom up. Its Pride Job Fair provides more than 100 employment opportunities for LGBTQ job-seekers. Pride Art brings together artists who explore self-identity and pride, some hailing from as far as New Zealand. The proceeds of Pride Run, which has an 180 yuan ($26) admission fee, go toward LGBTQ charities and the Gay Game, which holds once every four years.

“My impression that LGBTQ people are different faded as I interacted with them,” said Leyan, who volunteered for this year’s Pride Month. Still, he acknowledged that challenges remain due to low media exposure at the behest of the government. “The festival has certainly helped people build self-confidence. But it is more like an insiders’ party. I can’t say for sure that it has increased tolerance in general.”

Justin, a member of the Wharton Alliance, a LGBTQ pre-professional organization, was not surprised about ShanghaiPRIDE’s disbandment. Justin attended a LGBTQ parade at the Beijing 798 Art Zone years ago, where police blocked off the rally. “The video of policemen shoving two female volunteers to the ground made it to Weibo’s hot search list (微博热搜 weī bó rè sōu), but was taken down immediately,” he told The China Project.

Although official discrimination does not exist in China, the state has been restricting LGBTQ movements through a “don’t encourage, don’t discourage, don’t promote” policy. And those who dare to speak out risk being invited to tea talks. ShanghaiPRIDE’s suspension is yet another move by the government to constrain sex and gender minorities in the private sphere. This trend is disheartening. Public tolerance could fall further as awareness campaigns like ShanghaiPRIDE get shut down. For LGBTQ and other minorities in China, their struggle for acceptance still has a long way to go.