BRI at 10: China builds roads to combat its image problem in Central Asia

China wants to "tell its story well," but is that possible in a region where Sinophobia runs deep?

This is part 2 of our Belt and Road Dispatch.

- The role of Chinese companies

- China’s soft power ambitions

- China’s role in green technologies

- The Maritime Silk Road

When one thinks about China’s Belt and Road Initiative, it’s usually multibillion-dollar railroads that come to mind, not book fairs or entrepreneurship training. But the 2015 “Visions and Actions” document — which serves as the closest thing to a blueprint for the BRI — includes all of that. This document specifically mentions “people-to-people bonds” (民心相通 mínxīn xiāngtōng) as one of the five “Cooperation Priorities” (合作重点 hézuò zhòngdiǎn), alongside policy, facilities, trade, and financial cooperation.

Big roads are more visible and often more expensive than archaeological digs and youth exchanges, but people-to-people (P2P) connectivity is front and center of much Chinese writing about the BRI. State-owned enterprises are the engine of the Belt and Road, but they were active in the global economy long before the BRI’s launch in 2013. The new thing that the BRI accomplished was to package China’s global economic footprint under a single brand and sell it as a “global public good.”

Coinciding with his launch of the BRI, Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 also introduced the phrase “telling the Chinese story well” (讲好中国故事 jiǎng hǎo zhōngguó gùshì), spelling out Beijing’s ambition to foster a friendlier international environment by improving external propaganda. Through its P2P dimensions, as well as the development story it tells about China, the BRI is an instrumental part of China’s efforts to shape global narratives.

Sinophobia in Central Asia

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is now 10 years old. In 2019, I spent a year traveling overland from the U.K. to Vietnam, visiting Belt and Road projects and talking to people about the impact of China’s ambitions. This year, I marked the BRI’s anniversary by heading back out on the road to see what has changed.

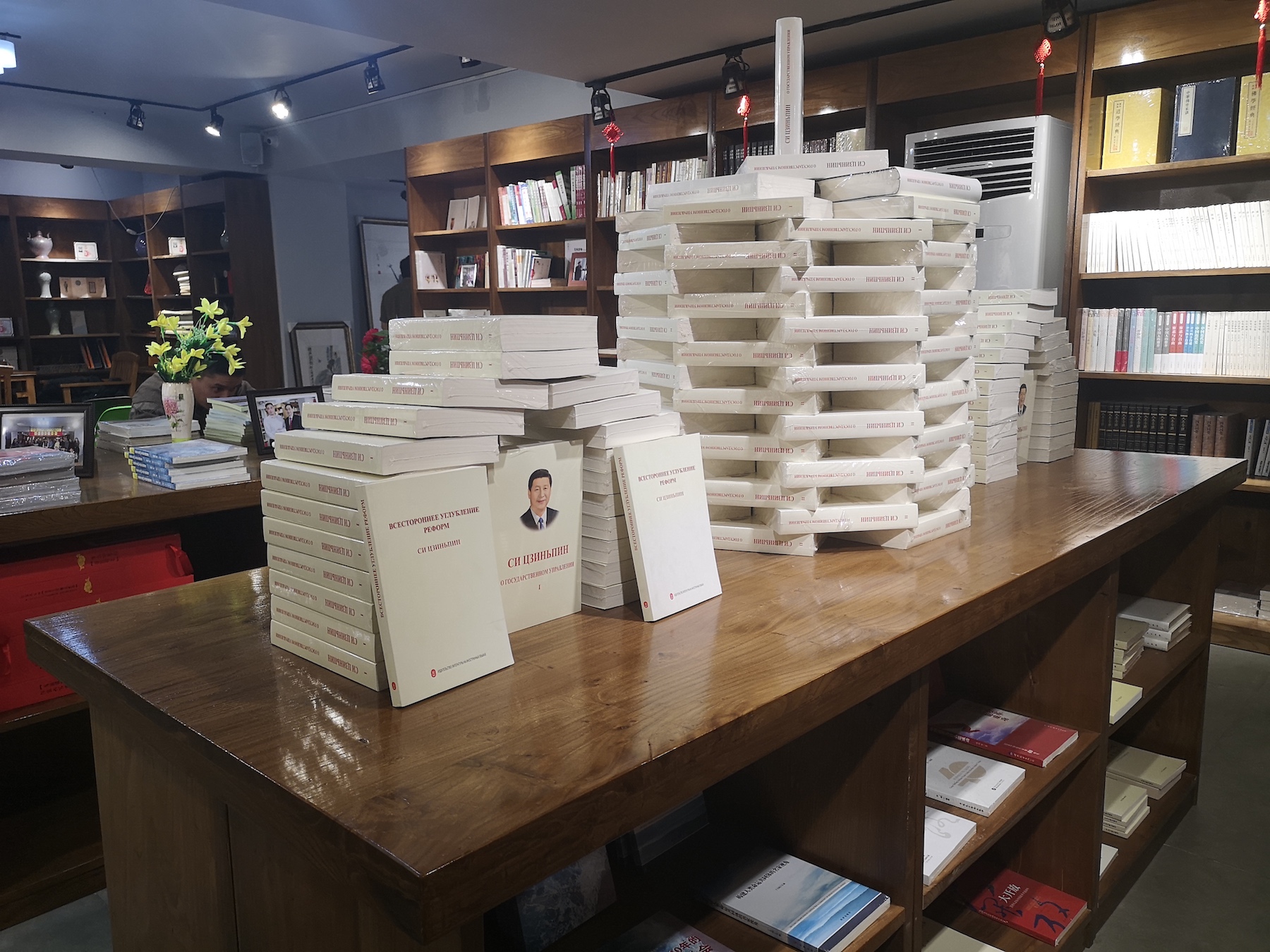

I arrived at a derelict storefront in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, in August 2023. The only sign that this was once a Chinese state media-sponsored bookshop is a pair of sun-faded Chinese lanterns and a giant, red character, 武 wǔ, in the courtyard. Peering into the storefront window, it’s difficult to see whether the owners took all their copies of Xi Jinping’s The Governance of China with them when they left.

This book — a weighty collection of Xi Jinping’s speeches — was the first thing that greeted visitors to Xinhua Bookstore’s “Chinese Cultural Exchange Center” back in 2019. The books were stacked meticulously on a table near the entrance, more for display purposes than for casual browsing.

At the time, the bookstore illustrated the sometimes ham-fisted nature of Chinese efforts to win hearts and minds in Central Asia. Four years later, derelict after closing during the COVID-19 pandemic, the bookstore symbolizes the fact that Beijing hasn’t made much progress in shifting public opinion in Central Asia. Nargiza Muratalieva, a Kyrgyz political scientist who researches public opinion on China, tells me, “Despite a list of new projects, China hasn’t shifted the dial in Kyrgyzstan.”

On special occasions in Kyrgyzstan, people still recite an epic poem about the hero Manas, whose legendary exploits mostly feature China as the principal enemy. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has attempted to co-opt the epic, interpreting the foe depicted in the poem as the Jungar, a people of Mongolian heritage, but in the Kyrgyz version, the villains are still Chinese.

Sinophobia in Central Asia runs deep. The empire to the East was always a traditional enemy of the nomadic Turkic tribes, and Soviet propaganda reinforced this narrative after the Sino-Soviet split. Although many people do hold legitimate concerns about the negative impacts of Chinese projects, interviews with locals about China, particularly in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, sometimes threaten to veer off into outright racism.

This negative perception of China has real-world effects for the Belt and Road Initiative. There have been dozens of anti-Chinese protests in Kyrgyzstan in recent years. In 2019, protests forced a Chinese-owned mine to halt operations, and a year later, anti-Chinese protests forced the government to scrap a planned $280 million logistics hub.

People-to-people efforts

Beijing is aware it has an image problem in Central Asia. Chinese officials do not publicly admit this fact, but Chinese commentators write euphemistically about the challenge of “eliminating fallacies” such as the “China threat theory” (中国威胁论 Zhōngguó wēixié lùn) in Central Asia.

In Kyrgyzstan, Chinese engagement in Kyrgyz media is at the forefront of Beijing’s “people-to-people” bond-building. Last year, the OSCE Academy in Bishkek published a report on Beijing’s “Soft Power Practice in Kyrgyzstan,” detailing China’s numerous agreements with Kyrgyz media and outreach to journalists. At the sidelines of the China-Central Asia Summit in May, Xi Jinping and the president of Kyrgyzstan signed four agreements on media cooperation, including one agreement on a joint TV series to be titled The Far Wind of the Silk Road.

Days after Xi held the China-Central Asia Summit in Beijing, the president of Xinhua sat down with Central Asian media representatives for a forum, at which, according to Xinhua, foreign representatives pledged to help China “create a favorable public opinion environment for mutually beneficial cooperation.” Outreach to media representatives and opinion shapers in Central Asia is insistent and extensive — it’s very common to hear from researchers or journalists who have been invited on an all-expense-paid trip to China.

However, these efforts don’t appear to be paying off yet. Results from the Central Asian Barometer survey indicate consistently negative feelings toward China in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, and increasing ambivalence in friendlier Uzbekistan.

Chinese Central Asia expert Lù Gāng 陆钢 suggests in a piece written after the May summit that China’s lack of progress in Central Asia is in part due to a confusion between external propaganda and true P2P bonds. “People-to-people bonds are simply understood as external propaganda,” he writes. Instead of “telling a few stories,” Lu Gang recommends that Beijing follow the U.S. in its “clever use of cultural soft power.”

Made in China

Beijing has more success in winning hearts and minds in Central Asia when external propaganda takes a back seat. Its most directly impactful P2P projects are the vocational training and Chinese-language programs it funds. There are 13 Confucius Institutes in Central Asia, and Beijing has also begun opening Luban Workshops in the region.

Luban Workshops are vocational programs that the Tianjin municipal government began building in 2016 under the BRI, and Central Asia is the new expansion ground. Workshops are opening or already open in all five of the Central Asian countries that attended the May summit. At a newly opened Luban workshop at the Tashkent State Transport University, the deputy rector of the university tells me confidently that “Chinese companies offer huge opportunities for our young people.” As of last month, though, when I visited, there is no new infrastructure or equipment behind this Luban Workshop, and the university official is mostly concerned with showing me footage of himself on Uzbek news. However, the university claims that equipment and a new building are forthcoming, and the program is at least having some concrete effects — a small handful of graduates have already been sent to Chinese companies.

Sentiment toward China is softer among younger people, and learning Chinese offers reasonable prospects for youth in Central Asia, either to find better-paying work in China or a job with a Chinese company in their home country. “Younger people see more economic opportunities with China,” says Zhanibek, who studied in China and now works as a consultant for Chinese companies in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.

However, while Kyrgyz students of Chinese may not share the Sinophobia of older generations, they are not naive about China. They are often aware of Beijing’s repression of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, for instance, though they feel powerless to affect the situation. The attraction to China is driven by economic opportunities more than anything else. “Culturally, we are not with China,” Zhanibek tells me, “people don’t think about China like that — it’s just a country we can do business with.”

Beijing’s most significant soft power asset is clearly the size of its economy and the story of its rise from developing country to superpower. The Chinese aphorism “to get rich, first build roads” best encapsulates the marketing strategy behind the BRI. Echoing Xi Jinping and Chinese state media, this is the phrase most commonly repeated by the builders of the BRI projects themselves. This is the Chinese Communist Party’s developmental philosophy — that infrastructure-led economic development is a necessary precursor to social stability and security.

When I ask Chinese workers in countries along the BRI in Eurasia a question like “What do you think of this place?” they often respond unenthusiastically — “Not very developed.” This is true even in Serbia, which is 63rd on the United Nations’s latest Human Development Report (a higher position than China itself). Chinese workers are in BRI countries first and foremost to make money for their families, but insofar as they feel a sense of mission, it is to share the gift of development. On the other side of the coin, when asked what they think of the Chinese, local people affected by these projects often respond the same way: “They’re good workers,” or “They get things done.” The seemingly universal cliche of the Chinese is that they are pragmatic businesspeople and efficient workers.

Of course, much depends on the impact of a BRI project, but when they are successful, Beijing receives a soft power bonus. Chinese infrastructure projects are often very Chinese, employing Chinese workers and using Chinese equipment, meaning that when things go right, they do so visibly. When a Chinese company built an important bridge in Croatia using EU funds, polling data shows that Beijing, not Brussels, enjoyed much of the soft power gains. Even when things don’t go well, citizens accustomed to inefficient and corrupt governments often blame their own, seeing the problem as endemic rather than imported.

More widespread adoption of high-end Chinese products is also shifting perceptions of China. Huawei phones and electric cars from BYD mean that “Made in China” is increasingly associated with high-tech, high-quality goods rather than cheap plastic and fakes. At one of the several BYD showrooms in Tashkent, a young salesman sits me down in a BYD Han and tells me that BYD cars are slowly shifting perceptions of “Made in China” in Tashkent. “Everyone is always surprised, they think the Chinese cars can’t be so good, but then they see the quality,” he says, running his hand across the car’s leather upholstery.

Beijing does its best storytelling when the story is backed by a high-tech car or shiny new bridge. Or, perhaps, when the story is told from beyond the state propaganda apparatus.

Zhanibek, the Bishkek consultant, feels that Beijing isn’t putting its best foot forward with its soft power efforts. He tells me, “Cultural cooperation is very poor, or very Chinese, if you get my meaning. It only comes through official channels and it’s very controlled — traditional dancing and singing.” Zhanibek would like to see more cooperation between Chinese and Kyrgyz youth organizations or NGOs. He’s actually co-authored and published a book about modern China, aimed at kids and the general public.

“It’s not propaganda,” he tells me. “The Chinese people understand Kyrgyzstan, but we don’t understand the Chinese — we can’t change our neighbors, so we have to try to better understand them.”

Zhanibek tells me that the Chinese approach is very slowly changing, but for now it seems that the most successful P2P initiatives in Central Asia have their foundation in genuine economic cooperation. The big question moving forward into the BRI’s second decade is whether China’s economic downturn might start to remove the shine from Beijing’s narrative of economic opportunity.