Chinese ex-premier Li Keqiang dies of a heart attack at 68

The former senior official was well liked at home and abroad, but in the New Era of Xi Jinping, Li was never more than China’s No. 2.

Former Chinese premier Lǐ Kèqiáng 李克强, a reform-oriented economist who was once a contender to the country’s top leadership role, died on Friday at the age of 68, less than a year after he stepped down from his post as China’s second-highest-ranking leader.

The newly retired official was in Shanghai when he experienced a sudden heart attack on Thursday. Despite “all-out rescue efforts,” Li passed away in the early hours of Friday, the official Xinhua News Agency said in a brief report, which didn’t provide further details.

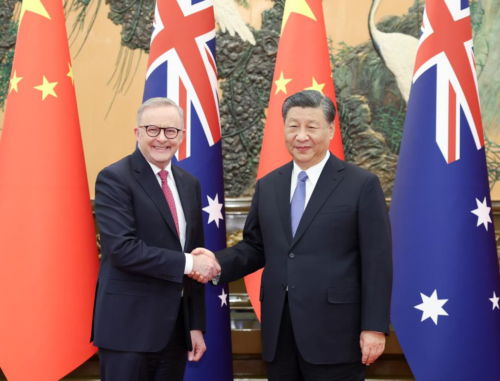

Li served as China’s premier — who typically heads the day-to-day government operations and runs the world’s second-largest economy — from 2012 to 2022 under Chinese President and Communist Party General Secretary Xí Jìnpíng 习近平. Li stepped down from the premier role in March after completing the maximum two terms in office, whereas Xi broke the tradition and secured his third term as the Party’s General Secretary. Li was replaced by Lǐ Qiáng 李强, one of Xi’s closest allies from his days in provincial government.

During the previous administration from 2003 to 2013, President and General Secretary Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛 and Premier Wēn Jiābǎo 温家宝 were seen as roughly equal in power, and state media devoted similar amounts of broadcast time and word count to covering both of them. But under Xi, Li Keqiang was always very much the second fiddle.

Humble origins

Born in July 1955 in Anhui Province in central China, Li was the son of a county-level Communist Party official. During the Cultural Revolution, he was dispatched to work in the rural areas of Anhui, where he spent multiple years performing manual labor before eventually assuming the role of his unit’s Party branch secretary.

During the 1980s, Li gained a reputation as a moderately liberal official by translating constitutional law texts written by a British judge. Subsequently, Li obtained a doctoral degree in economics under Lì Yǐníng 厉以宁, a prominent Chinese economist who is credited with laying the foundation for state-owned enterprise reform and the revival of the country’s stock market in the early 1990s.

After obtaining his Ph.D., Li quickly ascended through the Party ranks. By the early 2000s, he had run two provinces, Henan and Liaoning, both of which experienced strong economic growth under his leadership.

At the time, Li was seen as former leader Hu Jintao’s preferred successor as president. In 2017, Li was promoted into the seven-member Standing Committee, the most powerful political body in China. But five years later, in a then once-a-decade leadership reshuffle, the Party chose Xi for the top job and installed Li as premier.

Forever No. 2

During his decade-long tenure as China’s No. 2 official, Li spearheaded many of China’s efforts to shore up economic growth and remained a supporter of the global integration of China’s economy. But his influence was diminished as he was largely sidelined by Xi, who put himself in charge of nearly all aspects of policymaking. Li was a proponent of market-oriented reforms and private business, in contrast to Xi’s moves to expand state control over the economy.

Last October, as part of a reshuffle of China’s leadership, Li was dropped from the Communist Party’s all-powerful Politburo, despite being two years below the informal retirement age of 70.

As soon as the news of Li’s death broke Friday morning, Chinese social media was flooded with messages mourning him and reminiscing about the era he represented, one that was characterized by greater economic possibility, openness to private business, and a desire to keep the government’s power in check. On Weibo, a hashtag related to Li’s death garnered more than 2 billion views over the course of just a few hours. Many comments simply displayed emojis for candles and broken hearts.

Wáng Xiàngwěi 王向伟, former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post, wrote a short note titled RIP Li Keqiang, a man with a broken heart:

Waves of sadness and condolences are sweeping over China’s social media following the shocking announcement this morning of the sudden death of Li Keqiang, who just stepped down as PM in March. A dicey moment for China’s leadership at a time of uncertainty as they prepare for a critical plenary session of top CCP officials in the coming weeks. Li’s passing away came after sackings of China’s defense and foreign ministers as State Councillors. Judging by China’s recent history, the sudden death of a top leader could be a catalyst for change. Days after Jiāng Zémín 江泽民 died on November 30, China lifted zero-COVID restrictions.

As Wang suggests, there is already online speculation that Li’s death was not really caused by a heart attack, and that his death might provoke protests.

In contrast to the outpouring of grief from the public, China’s state-controlled media initially minimized the significance of Li’s passing. On major news websites, the 100-word official announcement about Li’s death was listed as the third or fourth top news item, trailing behind reports on Xi’s meeting with California Governor Gavin Newsom and Xi’s new publication on civil affairs initiatives.