Awakening ‘the lesbian factor’: Young Chinese women are ditching boyfriends and entering same-sex relationships

Frustrated by emotionally unavailable men, a growing cohort of educated young women in China are experimenting with dating other women, whom they say can better fulfill their emotional needs.

A college student at an art institute in China, Mia only dated boys and thought she was straight — until last fall, when she fell for a new schoolmate, a very handsome young woman who’s always dressed in simple but elegant black.

Mia often saw her around campus, walking with her drawing board clutched in her arms. One day, during a class presentation, Mia’s crush stood on the podium and lowered her head to check the computer. Her long, silky hair fell, gilded by golden sunlight.

“That is the first time I felt an attraction toward someone of the same sex,” said Mia, recalling the moment to The China Project.

Before developing a crush on this schoolmate, Mia had gotten out of an unpleasant relationship with a boy. After Mia’s ex-boyfriend learned about her newly found attraction to a woman, he felt so humiliated that he started spreading lies in their friend circles about how Mia was “insatiable” in bed.

“He called me a ‘public toilet,’ suggesting I’d sleep with anyone,” Mia said. “I think that’s just because me becoming a lesbian hurts his ego.”

According to Mia, the decision to turn away from heterosexual relationships stemmed from a combination of factors. For her, it is partly due to the more tolerant environment for queer individuals at her school. But more importantly, it is something Mia called “the lesbian factor.”

“I think if you have the lesbian factor, then you can become a lesbian when the time is ripe,” she added.

While sexuality is known to be fluid, “the lesbian factor” points to the moment when women break free from the pervasive cultural expectation that they should be attracted to men and be assertive about what they want in a relationship. As more and more educated young Chinese women embrace feminism, they have also become increasingly mindful and critical about toxic masculinity or “straight men cancer” (直男癌 zhínánái).

In our interviews with Chinese young women in their early twenties, many shared the observation that some of their female friends seemed to have “turned gay” overnight. Many attributed this transformation to a general dissatisfaction with the status quo of China’s gender dynamics.

“Men are emotionally unavailable”

Layla, who also used to date boys, recounted to The China Project how her “last and final heterosexual relationship” — with a guy who “looked perfect on paper” — fell apart.

“He had a good reputation among our schoolmates and a good personality. He also was muscular, which I thought was attractive,” Layla said. But soon, she found out that she couldn’t communicate with him at all. “He religiously sent me messages such as ‘good morning’ and ‘good night.’ But when I asked him for help one night, he simply ignored my question but continued to greet me the next morning. He was like a talking alarm.”

The inconsistencies in communication provoked Layla’s doubts about the relationship and prompted her to search for a spiritual connection, which she later found when dating her current partner, a girl who is two years younger than her. “Although we live in different cities, we talk constantly,” Layla said. “We text during the day and get on the phone for two hours at night. She really is an important part of my life.”

Echoing Layla’s feelings, Mia said it was hard to have her emotional needs fulfilled when dating the opposite sex. “The men I dated didn’t know how to express themselves. They couldn’t deal with emotional issues, so they chose to bury them. But they would bring them up again in a fight long afterward. It was exhausting,” she said.

By contrast, Mia can now communicate at ease with her current girlfriend, who goes to the same school as she does. Dating a girl also comes with “extra perks,” Mia said. “Girls understand social appearance anxiety. When I was with my ex-boyfriend, I constantly worried if I would look bad with makeup. But now I can just be myself.”

“Love knows no gender”

For this contingent of mostly young women, social media has provided them with a greater opportunity to be a part of supportive communities. On Douyin, the Chinese sibling of TikTok, Gladys, who once self-identified as straight before having her lesbian awakening, has racked up more than 30,000 followers by posting about her daily interactions with her current girlfriend.

According to her, although the Chinese government has become more intolerant and homophobic in recent years, her experiences on the app have been overwhelmingly positive. “My friends and followers are all very supportive. They are just curious about what it feels like to date a girl, which I don’t mind sharing,” she told The China Project. But Gladys is also aware that this is because she interacts exclusively with young people, whom she believes are more liberal. She does not think that her parents and relatives would understand the change in her sexuality, and does not plan on telling them.

Coming out as lesbian is not a positive process for everyone, though. For Hannah, her relationship with her parents deteriorated rapidly when they found out that she started dating girls. She also lost her job in part due to her sexuality. “After my supervisor knew I was gay, she verbally and physically harassed me. I had to put up with her for the sake of my career. But then she started deducting my salary, telling me that me being a lesbian was ‘not good for the image of the company,’” she told The China Project. The discrimination forced her to leave the company eventually, but she doesn’t think it was entirely about her sexuality. “When there is a conflict, people will do anything to pick on you. Sexuality was just an easy target in China.”

Despite the obstacles, these Chinese young women are striving to lead a life with the ones they love. Layla said that she had no plans of “turning back to straight.”

“I know that some see this as just a phase, after which you need to return to your ‘normal life.’ But for me this is a journey of self-discovery. I managed to shed the values that society forced upon me, and explore how I really feel,” she said.

All of the people interviewed for the story requested not to use their full names out of concerns for privacy.

Other LGBTQ stories:

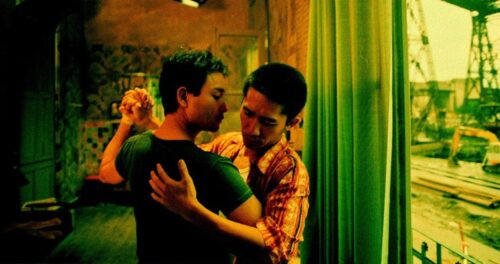

“Love Is Love” LGBTQ+ film festival. (Netherlands Embassy in China)

Co-organized by 15 general consulates in Guangzhou, including the U.S., Canada, the U.K., Brazil, the Netherlands, and Mexico, the film festival took place from June 6 to June 30. As one of the very few queer events that was allowed to occur in China during this year’s Pride Month, the festival offered screenings of a variety of international LGBTQ+ films and was free to the public.

China’s LGBT community doesn’t need Western “gay pride” (South China Morning Post)

“For LGBT people in China, sexuality is part, not all, of who they are as their familial role and national identity take precedence. What they want most is love and acceptance, not pride parades.”

Activist detained in Hong Kong begins final appeal for recognition of his overseas same-sex marriage (AP)

In a landmark case for the city’s LGBTQ+ community, an activist detained in Hong Kong began his final appeal in late June seeking recognition for his same-sex marriage registered overseas.

Queer China is our fortnightly roundup of news and stories related to China’s sexual and gender minority population.